Highworth Markets and Fairs

Highworth is located where a Saxon royal estate once existed and where its hundred courts were held every four weeks. By the 11th century a minster church had also been established. Lay settlements would have converged here attracting and encouraging trade. It is this pre-urban nucleus which provided a centre and ready market for the early borough of Highworth until it gained an economic life of its own.

The 12th and 13th centuries, particularly, witnessed the establishment of new towns in England. Feudal lords were all involved in laying out planned towns with burgage plots on their manors with an adjacent market. Warin FitzGerold, whose family had held the hundred of Highworth since 1156 and who was lord of the manor of Sevenhampton, was influential in the founding of our town. One of the prime functions of a town was to act as a market and exchange for its hinterland. The acquisition of a market charter was essential for the medieval town to survive and develop. Charters authorising the holding of a weekly market and annual fairs, often conveying the privileges of borough status, had to be purchased from the king. They were considered to be a profitable investment. To get a charter one needed influence at court. As hereditary chamberlain to both King Richard and later King John, FitzGerold, whose name appears on the Magna Carta, was in a unique position to achieve this goal.

The 12th and 13th centuries, particularly, witnessed the establishment of new towns in England. Feudal lords were all involved in laying out planned towns with burgage plots on their manors with an adjacent market. Warin FitzGerold, whose family had held the hundred of Highworth since 1156 and who was lord of the manor of Sevenhampton, was influential in the founding of our town. One of the prime functions of a town was to act as a market and exchange for its hinterland. The acquisition of a market charter was essential for the medieval town to survive and develop. Charters authorising the holding of a weekly market and annual fairs, often conveying the privileges of borough status, had to be purchased from the king. They were considered to be a profitable investment. To get a charter one needed influence at court. As hereditary chamberlain to both King Richard and later King John, FitzGerold, whose name appears on the Magna Carta, was in a unique position to achieve this goal.

On the 20th April 1206, the first known charter giving the right to hold a weekly Wednesday market and an annual fair at Highworth on the vigil and feast of St Michael (29th September) was granted to FitzGerold, by King John. This charter is amongst the earliest of Wiltshire’s market charters, possibly the tenth oldest. This right has continued in the town into the twenty first century.

Ownership of the markets and fairs was a valuable perquisite which could be bought and sold. Sound economic reasons lay behind the purchase of these vital documents: rents from market stalls, tolls paid on goods brought into the borough and market place, fines levied in the markets and borough courts and seigneurial monopoly of prices all generated a substantial cash income for the owners of these charters.

At about this time Highworth was granted its Borough Charter. Certain commercial freedoms were usually included, notably exemption from tolls to the freemen of the town. This lessened their costs and increased their potential profit putting the townsmen at an advantage and the outsider at a disadvantage in buying and selling. A later grant to hold an annual fair on the feast of St Peter ad Vincula (1st August) was made to FitzGerold’s great grandson, Baldwin de Redvers, 8th Earl of Devon, by King Henry III on 12th June 1257.

We know from a survey of the manor of Sevenhampton, made in 1274/75, that the lease of the windmill, market and fair of Highworth brought in an annual income of £10.00 to the landlord. The average weekly wage at that time was 4d (1.66p.) By the end of the 13th century Wiltshire had 49 market towns which held a total of 55 fairs.

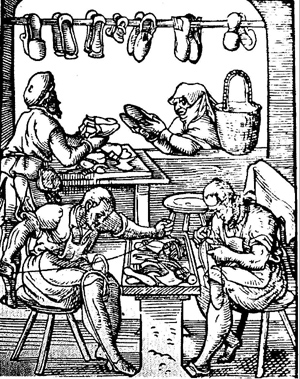

The appearance of the medieval marketplace itself would have been very different from that of today. It would have been much larger, completely open in the centre and bordered by the buildings to the north of Sheep Street and the south of the High Street. The buildings now to be seen on the north side of the High street and in the centre of the market place are later infills and encroachments and indicate the success of the market town which attracted more craft and tradesmen to live there.

There is evidence that Highworth was involved in England’s wool and cloth trade; references to mercers, staplers, fullers, dyers and shearers appear frequently in many of the records relating to Highworth over a long period of time. In August 1365, Thomas Hungerford granted away much of his land in the area, ‘except a shop called Shereresshoppe in Heygworth’. Shearing was the last process in the production of cloth. Hungerford obviously took great care that this property did not pass from his control. It is possible that this cloth would have been sold at the markets or fairs to local traders or possibly even to overseas buyers.

Highworth had its market cross, probably set up at the time of the granting of the market’s charter in 1206. The survey of 1275 mentions a white cross adjacent to Market Street. A document dated 1684 tells of ‘a Cross which is the principall part of the markett’ whilst in 1821 there is a further mention ‘over against the site of the Market House there where the high cross formerly stood’. The cross declared the authority of the market and provided a focal point from which the assembled traders and townspeople could be addressed by market officials and itinerant preachers.

By 1547 Thomas, Lord Seymour gained possession of the Hundred and Borough of Highworth, together with its fairs and markets, when he married the widowed queen Catherine Parr who had been granted them for her life as part of her dower when she married King Henry VIII.

Leland, the antiquarian, writing in the mid sixteenth century relates that:

‘I lernid of certentye that a mile out of Faringdon, toward the right way (to) Highworth toune V miles from Faringdon wher is a good market for Barkshir on the Wensday’.

In the 1580s John Warneford and John Stock are recorded as growing woad in Sevenhampton, Eastrop and Lint. Woad was used in the cloth dyeing trade and some of their goods would probably have passed through Highworth market.

Inns, always a good indicator of the activity and success of a market town, were centres of commercial activity where wholesale dealings often went on. Highworth, in 1607, had at least twelve inns pointing to its standing as an important and thriving market town. Ale was also allowed to be sold from bush houses during the markets and fairs; Highworth had at least two of these in Sheep Street and at the east end of the High Street.

In the first half of the 17th century Highworth experienced major economic and social difficulties. In the 1630s outbreaks of plague had occurred in the town and the surrounding area, resulting in trade moving to nearby towns.

John Aubrey, writing of Swindon in 1672, says ‘here is on Munday every weeke a gallant markett for cattle, which increased to its now greatnesse upon the plague of Highworth, about 20 years since’.

During the Civil War of 1642-1649 Highworth was garrisoned initially by the King from April 1644 to June 27th 1645 when it fell to the Parliamentarians who occupied it through to October 1646. The presence of troops in the area discouraged traders from attending the market and business drifted away to other more peaceful places.

A Parliamentary intelligence report for Wednesday 17th May 1643 states “the butchers which were wont to kepe their markets at Highworth and other places thereabouts cannot now passe without having both their oxon and sheepe taken from them by the Cavallyers”.